What happens when you switch on your computer? Facts that most computer science engineers are never taught!

20 October 2014 By Bhavyanshu Parasher

Overview

So you have graduated in computer science and yet you fail to understand how computers actually boots up? Not an issue because we are never taught about these basics in college. Atleast I never was! I still remember my operating system class where we were taught about bootstrapping but that too in a very vague and casual manner, it left lot of questions in my mind, can’t say about anyone else, like where does the very first instruction resides? How is that instruction moved to main memory for execution? It’s not like we have an operating system to manage everything when we have just switched on the computer. To answer this, our teachers very casually say that it resides in the BIOS and from there everything begins. We are taught everything as if computers work on magic and not science.

I have taken the pain to write this post not to prove how insanely stupid our education system is but to do a write up of my own knowledge gained through reading books and online documents so that I can remember it and refer to this in case I ever again get a question about the boot sequence and the steps that take place as soon as we power on the computer. This post is also for CS engineers who admit that they don’t understand how a computer boots up. Simple!

Let’s get started

To understand boot sequence, we must look back a few years and understand how Intel’s 80x86 was made to boot up, then only we can learn how modern day computers boot up. Bootstrap is a term that refers to a person who tries to stand up by pulling his own boots. So if we compare this to the computers, it simply means that bootstrap is that program (possibly a portion of operating system) which must be brought into main memory for execution by the CPU so that processes can be created.

System Start-up Phase

At the time when computer is powered on, every component is in its random unpredictable state. For example, the RAM modules contain random data which must be flushed out. To do this, there is a RESET pin available on the processor circuit, which when raised to a higher logical value, sets some registers, for example, cs and eip, to some fixed values and executes the code at 0xfffffff0 physical address. Actually this address is mapped by hardware to ROM (Read-Only Memory) and this code is nothing but the first instruction of BIOS (Basic Input/Output System). Here I would like to clear out a misconception, that I believe might be a misconception of many.

Q.) Aren’t BIOS stored on CMOS? If it is on ROM, then how are we able to overwrite BIOS settings?

Ans. The question in itself is very vague because we all know that ROM is read only and cannot be simply written to. Actually, the BIOS settings are stored on the CMOS which can be modified by the user by accessing the BIOS interface whereas, the BIOS program is stored in EEPROM so the ROM being EEP means that the BIOS can be updated.

Real Mode - BIOS must require use some addressing mode as well. Since Real mode addresses are the only ones available when the computer is powered on, so BIOS must make use of Real mode addresses. Since there is no Global Descriptor Table or paging table is available at the time of boot, there is no provision of computing logical addresses into physical addresses. A real mode address, in 80x86 architecture, is computed using, segment and offset by \(seg*16+off\). You can read more about Real Mode.

Now the BIOS procedure performs various tasks like :

- Power On Self-Test (POST) - Checks which devices are present and whether they are functioning properly or not. If the BIOS is an ACPI (Advanced Configuration and Power Interface) compliant, then it builds several tables which store information of the devices that are present. These are used by operating system later on.

- Test PCI devices and create a table for PCI devices

- Search for operating system - Again, this is a very vague statement because this makes it sound so easy. Let us see what actually happens in this phase and how BIOS is able to find and load portion of operating system into main memory for execution.

The Boot Loader Phase

As we know that the hard disk is divided into sectors, the sector 0 of the hard disk, which is the first sector, is called MBR (Master Boot Record), which has a partition table and code. The default code part, if unmodified, identify the partition with a bootable kernel image by an active flag in the partition table, telling it to load the kernel image stored in the active partition only whereas, in case we have installed linux in some partition, the partition table remains the same but the code part of MBR is replaced by a more flexible program called - the Boot Loader - that lets user choose what operating system to boot into. Now, if you are a linux user, you must have heard of the words GRUB and LILO while dual booting linux with windows? This GRUB(GRand Unified Bootloader) is written over the code part of the MBR, which is why when you dual boot, you are presented with an option to choose an operating system to boot into. The partition table is of 64 byte with 4x16byte entries. As we have seen how MBR works in case of windows, the linux bootloaders, GRUB and LILO, work in a very different manner and, according to me are very powerful and flexible. Actually GRUB and LILO are quite big that they cannot fit into single sector at once. So it has to be divided into parts called stages. The first stage is in the MBR itself, called Stage 1. Stage 1 is enough to load another sector which may be the boot sector for a partition. These two read a file containing the Stage 2. This file is commonly known as grub.conf or boot.ini in case of Windows. This is responsible for presenting users with an option of choosing what operating system to boot into. Now as soon as user selects an operating system from the options, the boot loader must be able to find the kernel image and move a small portion of kernel into main memory for the execution to begin. This small portion of code is called Kernel bootstrap code. This also marks the end of the boot loader phase.

Kernel Initialization Phase - Giving life to the Operating System

The processor is still in Real Mode with paging disabled and can only address 1 MB of memory. After going through last section, you might be wondering that if the processor can only address 1 MB of memory then how can it map the kernel image which is huge in size as compared to what real mode can handle. The answer to the question is unreal mode. Unreal mode consist of breaking the 64K (There is a barrier of only being able to use 64K beyond 1 MB with just A20 gate active) limit of real mode segments, but still keeping 16 bits instruction and \(segment*16+offset\) address formation by tweaking the descriptor caches. There is an excerpt I would like you to read. It is taken from codeproject.

A ‘bug’ in the 80386+ processor turned out to be a feature called unreal mode. The unreal mode is a method to access the entire 4GB of memory from real mode. This trick is undocumented, however a large number of applications (including HIMEM.SYS) are using it.

Enable A20.

Enter protected mode.

Load a segment register (ES or FS or GS) with a 4GB data segment.

Return to real mode.

As long as the register does not change its value, it still points to a 4GB data segment, so it is possible to use it along with EDI to access the entire address space. 80286 lacks this capability because to exit protected mode, the CPU has to be reset, so all registers are destroyed.

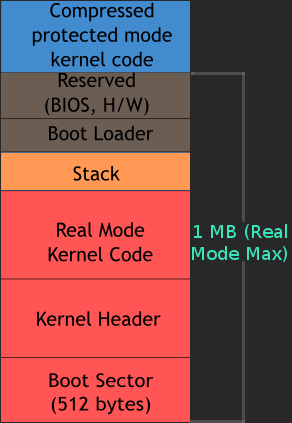

By the end of this, we would still be in real mode only and some amount of compressed protected-mode kernel code is brought into the main memory which is usually loaded high and real-mode kernel code (very small as compared to the protected-mode kernel code) is loaded low in RAM. At this point there are many other things like, stack, kernel header fields, boot sector etc in the main memory. Now that the job of boot loader is done, it is the task of kernel bootstrap to begin execution. The first action takes place inside the real-mode kernel code which is already in RAM, as stated above. The boot sector code plus the read-mode kernel header make up the 512 bytes. Look at the image shown below to understand better. When an offset of 0x200 (This value is fixed) is added, we get our very first instruction which is of the linux kernel, called the kernel entry point. From here on there is a jump to the routine called setup() in header.S file. This routine initializes segment register, stack, zeroes the bss segment so that static values start with zero and then finally jumps to main() function in main.c. This marks the end of real mode as well. Now, the processor must be switched to protected mode but before that the Interrupt Descriptor table and Global Descriptor Table must be moved to their actual locations because in real mode IDT is always at location 0 in memory. There are dedicated registers which must be updated, namely IDTR and GDTR as soon as the protected mode switch routine is called.

Protected mode phase

As soon as the protected mode routine is called, the PE bit of the CR0 register is set and now finally we can address complete 4 GB of memory again. In protected mode there is no restriction on memory. The next instruction to be executed is startup_32() which again initializes some registers and since the kernel is still in compressed form, it calls decompress_kernel() to decompress the kernel image. Once done, it moves this decompressed kernel to 0x00100000 physical address. Next entry point is this physical address only, which is another startup_32() (in kernel/head.S file) code and is different in every way from previous one, it basically does the following :

- sets up registers for protected mode and builds final IDT, loads idtr and gdtr registers with addresses of IDT and GDT.

- enables paging by setting PG bit in CR0 register,

- stores the address of the Page Global Directory in the CR3 register,

- initialzes stack, clears eflags register, invokes setup_idt(), puts system info from the BIOS to the first page frame, and

- finally, most important, it sets up the execution environment for the first kernel process, Process 0.

After all this, it jumps to start_kernel() entry point. start_kernel() is the final step in initializing the kernel. I cannot explain all the tasks here but I will just name a few :

- Calls sched_init() which initializes the schedules, as the name suggests.

- Initializes buddy system allocators, memory zones by respective function calls.

- IDT is initialized by trap_init() function call and init_IRQ() call.

- System data and time is initialized by time_init(), CPU clock speed is determined by caliberate_delay(), and

- The kernel thread for process 1 is created by kernel_thread(). This thread is responsible for forking other threads, which leads to execution of /sbin/init.

At the end of this, you are presented with a login prompt, letting user know that the kernel is up and running. That’s all. So as you can see that the bootstrapping procedure is rather complex procedure, it still makes us feel as if everything happens so quickly. Even I have not completely explained each and every step in detail but I hope by reading this you might have got some idea on what happens when you power on your computer.

Correct me if I am wrong anywhere. These concepts are purely based on my research, on my knowledge and understanding of this topic and from various books, wikis and published documents.

References

- Unreal Mode

- Understanding the Linux Kernel by Daniel P. Bovet & Marco Cesati

- x86 Wiki

- 80x86 Boot State Specifications

blog comments powered by Disqus