Linux Device Drivers Part 1

17 November 2013 By Bhavyanshu Parasher

Overview

Since we know that the linux kernel code is huge and complex in itself, the kernel hackers need an entry point to the code without thinking of the complexity. The device drivers act as an entry ramp into the code house of linux kernel. Basically they are black boxes that make a particular piece of hardware respond to a well defined internal programming interface. The device drivers are plugged in only at runtime and are seperated from the kernel in such a way. The rate at which new hardware comes in the market, the demand for device driver for that specific hardware increases. As the hardware vendors want to reach out to a huge community of linux users as well.

What a linux device driver developer must be careful about?

When writing drivers, a programmer should pay particular attention to the concept that they can write code to access the hardware but should not force particular policies on the user since different users have different needs. A flexible driver is one that offers access to the hardware capabilities without adding any kind of restrictions. It is the software layer between the actual device and the applications. The drivers are usually based on two switches : Policy-based & Mechanism-based/Policy-free. In policy-free drivers, we have the support for syn & async operations, the ability to use the capabilities of the hardware to the extreme. This type is easy to write and maintain and works better for end users. But even in policy-free, packages are distributed with default configuration files.

Difference between kernel module and application

It’s also worth underlining the differences between the kernel module and an application. The kernel modules are event driven. For example, the module may be once called but once it exits, it the module just says “I am not here anymore, Don’t send me further requests”. Whereas not all applications are event driven. The another big difference is that the kernel module may release all its resources at once but the application maybe lazy in releasing its resources. The exit function of the module must carefully undo everything the init function has built up in the beginning.

In case of modules, the ability to unload a module is pretty easier than going through the reboot cycle everytime you make a change.

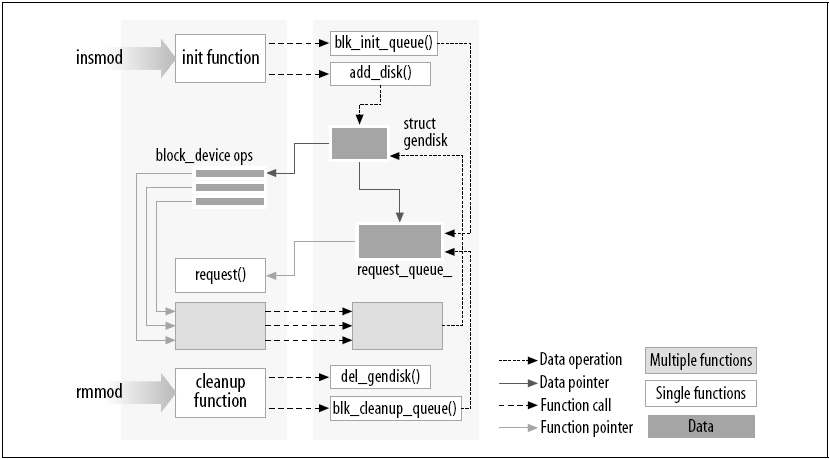

Figure below shows how functions calls are used to add new functionality to the kernel.

It is important to note that only functions which are actually a part of the linux kernel maybe used in kernel modules. No library should be linked to modules. Most of the relevant headers live in include/linux and include/asm and other dirs in include have been added to host material specific to kernel subsystems.

User Space & Kernel Space

User Space runs the applications and Kernel space runs the modules. This is the basic idea of current operating systems. Did you know that the CPU itself has implementation of different operating levels? That’s right. In Unix, the kernel executes in the highest level called the supervisor mode where everything is legal whereas the applications run in the lowest level called the user mode where the processor regulates direct access to hardware.

Stack Size

The applications use very large stack area as compared to kernel modules. The kernel has a very small stack. It can be as small as a single 4096 byte page. In case you need larger structures, you must build them dynamically at call time. It is very unpleasant to declare large variables right at the beginning.

Concurrency Concept

The applications might run sequentially and be unaware of the changes in the envrionment but that’s not the case with the kernel. Kernel code does not run like that. The kernel module developer must be aware that there might be many things happening around while the module is being executed. The data structures used must be designed so carefully to keep multiple threads seperate and the shared data should be carefully used in order to prevent corruption. The techniques used for this will be explained later as i go on writing this tutorial series.

Although kernel modules don’t execute sequentially, most actions performed by the kernel are done by a process. Kernel code accesses the current process using <asm/current.h>, which yeilds a pointed to struct task_struct defined by <linux/sched.h>. This will also be used in detail later.

( __ functioname __ ), what the hell is this?

This basically tells the developer that “I am a very dangerous function and only use me if you really know what you are doing”. Yup, it’s one badass type function. These generally are the llow-level component of the interface.

That’s it. I guess this is enough theory for now. Let us get on with writing our first module in the next part.

blog comments powered by Disqus